By Roy Cook

The

war between the United States and Mexico had two basic causes.

1. First,

the desire of the U.S. to expand across the North American continent, the

policy of Manifest Destiny, to the Pacific Ocean caused conflict with all

of the U.S. neighbors; from the British in Canada and Oregon to the Mexicans

in the southwest and, of course, with the Native Americans, many on U.S. treaty secured lands.

2. The

second basic cause of the war with Mexico was the Texas War of Independence

and the subsequent annexation of that area to the United States.

After the beginning of hostilities, the

U.S. military reported to the President and it became apparent to the Polk

Administration that only a complete battlefield victory would end the war.

Continued fighting in the dry deserts of northern Mexico convinced the United

States that an overland expedition to capture of the enemy capital, Mexico

City, would be hazardous and difficult. To this end, General Winfield Scott

proposed what would become the largest amphibious landing in history, (at

that time), and a campaign to seize the capital of Mexico. The Marine Corps

still recognizes this landing in the first line of the Corps' hymn: From the Halls of Montezuma.

One

interesting aspect of the war involves the fate of U.S. Army deserters of

Irish origin who joined the Mexican Army as the Batallón San Patricio (Saint

Patrick's Battalion). This group of Catholic Irish immigrants rebelled at

the abusive treatment by Protestant, American-born officers and at the treatment

of the Catholic Mexican population by the U.S. Army. At this time in American

history, Catholics were an ill-treated minority, and the Irish were an unwanted

ethnic group in the United States. In September 1847, the U.S. Army hanged

sixteen surviving members of the San Patricios as traitors. To this day, they

are considered heroes in Mexico.

The story of

this famed group begins with the founder and chief conspirator, John Riley,

a Galway native born in 1817. Riley deserted from the British army while stationed

in Canada and went to Michigan, where he later enlisted in the US Army in

1845. He was able to defect to the Mexican Army when his commander granted

him permission to cross into Mexico to attend mass. It was there, in Matamoros,

Riley joined the Mexican Army as a lieutenant, which resulted in his pay rising

from seven dollars per month to 57 dollars per month. While desertion from

the US armed forces was punishable by death, Riley was not deterred in capitalizing

on the dis-satisfaction of many Irish-born US soldiers with their adopted

country. Aided by his second-in-command, Patrick Dalton, who was from the

parish of Tirawley, near Ballina, County Mayo, Riley at first was successful

in persuading 48 Irishmen to defect, and these men made up the original Saint

Patrick's Battalion. In addition to more Irishmen joining, they welcomed other

foreign-born US deserters, as well as American-born deserters. Also, some

Irish-born civilian residents of Mexico were persuaded to join the struggle.

Even when the number of San Patricios rose to more than 200, Irish-born members

still represented nearly 50 per cent.

The story of

this famed group begins with the founder and chief conspirator, John Riley,

a Galway native born in 1817. Riley deserted from the British army while stationed

in Canada and went to Michigan, where he later enlisted in the US Army in

1845. He was able to defect to the Mexican Army when his commander granted

him permission to cross into Mexico to attend mass. It was there, in Matamoros,

Riley joined the Mexican Army as a lieutenant, which resulted in his pay rising

from seven dollars per month to 57 dollars per month. While desertion from

the US armed forces was punishable by death, Riley was not deterred in capitalizing

on the dis-satisfaction of many Irish-born US soldiers with their adopted

country. Aided by his second-in-command, Patrick Dalton, who was from the

parish of Tirawley, near Ballina, County Mayo, Riley at first was successful

in persuading 48 Irishmen to defect, and these men made up the original Saint

Patrick's Battalion. In addition to more Irishmen joining, they welcomed other

foreign-born US deserters, as well as American-born deserters. Also, some

Irish-born civilian residents of Mexico were persuaded to join the struggle.

Even when the number of San Patricios rose to more than 200, Irish-born members

still represented nearly 50 per cent.

Looking

back, to the motivation for the policy of Manifest Destiny, we need to examine

President Jefferson's acquisition of the right to treat with the Indian Nations

for land in Louisiana Territory in 1803, Americans illegally migrated westward

in ever increasing numbers, very often into lands not belonging to the United

States. By the time President Polk came to office in 1845, this idea, based

on racist principals called "Manifest Destiny", had taken root among the American

people, and President Polk was a firm believer in the idea of expansion. The

belief that the U.S. basically had a Euro-centered God-given right to occupy

and "civilize" the whole continent gained favor as more and more Americans

invaded the western lands. The fact that most of those areas already had Tribal

people living upon them was usually ignored, with the attitude that democratic

English-speaking America, with its high ideals and Protestant Christian ethics,

would do a better job of running things than the Native Americans or Spanish-speaking

Catholic Mexicans.

Manifest

Destiny did not necessarily call for violent expansion if the land can be

bought cheap. In both 1835 and 1845, the United States offered to purchase

California from Mexico, for $5 million and $25 million, respectively. The

Mexican government refused the opportunity to sell half of its country to

Mexico's most dangerous neighbor. Many

Americans opposed what they called "Mister Polk's War." Whig Party members

and abolitionists in the North believed that slave-owners and Southerners

in Polk's administration had planned the war. They believed the South wanted

to win Mexican territory for the purpose of spreading and strengthening slavery.

This opposition troubled President Polk. But he did not think the war would

last long. He thought the US could quickly force Mexico to sell him the territory

he wanted.

Polk

secretly sent a representative to former Mexican dictator Santa Ana, who was

living in exile in Cuba. Polk's representative said the United States wanted

to buy California and some other Mexican territory. Santa Ana said he would

agree to the sale, if the United States would help him return to power. President

Polk ordered the US Navy to let Santa Ana return to Mexico. American ships

that blocked the port of Vera Cruz permitted the Mexican dictator to land

there. Once Santa Ana returned, he failed to honor his promises to Polk. He

refused to end the war and sell California. Instead, Santa Ana organized an

army to fight the United States.

Not

all American westward migration was unwelcome. In the 1820's and 1830's, Mexico,

newly independent from Spain, needed settlers in the under-populated northern

parts of the country. An invitation was issued for people who would take an

oath of allegiance to Mexico and convert to Catholicism, the official religion.

Thousands of Americans took up the offer and moved, often with slaves, to

the Mexican province of Tejas (texas). Soon however, many of the new "Texicans"

or "Texians" were unhappy with the way the government in Mexico City tried

to run the province. In 1835, the Tejanos revolted, and after several bloody

battles, the Mexican President, Santa Anna, was forced to sign the Treaty

of Velasco in 1836 This treaty

gave Tejas (texas) its independence, but many Mexicans refused to accept the

legality of this document, as Santa Anna was a prisoner of the Tejanos at

the time. The Republic of Tejas (texas) and Mexico continued to engage in

border fights and many people in the United States openly sympathized with

the U.S.-born Texans in this conflict. As a result of the savage frontier

fighting, the American public developed a very negative stereotype against

the Mexican people and government. Partly due to the continued hostilities

with Mexico, Texas decided to join with the United States, and on July 4,

1845, the annexation gained approval from the U.S. Congress.

Official Military campaign accounts: The

"Army of Observation" commanded by General Zachary Taylor was deployed to

Corpus Christi, at the mouth of the Nueces River, to protect newly annexed

Texas in the summer of 1845. The force consisted of 5 regiments of infantry,

1 regiment of dragoons, and 16 companies of artillery. After the beginning of hostilities, the

U.S. military embarked on a three-pronged strategy designed to seize control

of northern Mexico and force an early peace. Two American armies moved south

from Texas, while a third force under Colonel Stephen Kearny travelled west

to Sante Fe, New Mexico and then to California. In a series of battles at

Palo Alto and Resaca de Palma (near current-day Brownsville, Texas), the army

of General Zachary Taylor defeated the Mexican forces and began to move south

after inflicting over a thousand casualties. In July and August of 1846, the

United States Navy seized Monterey and Los Angeles in California. In September,

1846, Taylor's army fought General Ampudia's forces for control of the northern

Mexican city of Monterey in a bloody three-day battle. Following the capture

of the city by the Americans, a temporary truce ensued which enabled both

armies to recover from the exhausting Battle of Monterey. During this time,

former President Santa Anna returned to Mexico from exile and raised and trained

a new army of over 20,000 men to oppose the invaders. Despite the losses of

huge tracts of land, and defeat in several major battles, the Mexican government

refused to make peace.

On

March 9, 1847, General Scott landed with an army of 12,000 men on the beaches

near Veracruz, Mexico's most important eastern port city. From this point,

from March to August, Scott and Santa Anna fought a series of bloody, hard-fought

battles from the coast inland toward Mexico City.

Churubusco, 20 August 1847.

Santa Anna promptly made another stand on Churubusco where he suffered a disastrous

defeat in which his total losses for the day "killed, wounded, and especially

deserters" were probably as high as 10,000. Scott estimated the Mexican

losses at 4,297 killed and wounded, and he took 2,637 prisoners. Of 8,497 Americans

engaged in the almost continuous battles of Contreras and Churubusco, 131 were

killed, 865 wounded, and about 40 missing.

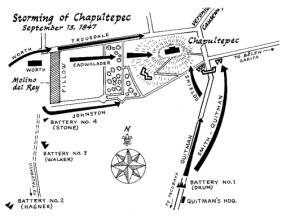

Scott

proposed an armistice to discuss peace terms. Santa Anna quickly agreed; but

after two weeks of fruitless negotiations it became apparent that the Mexicans

were using the armistice merely for a breathing spell. On 6 September Scott

broke off discussions and prepared to assault the capital. To do so, it was

necessary to take the citadel of Chapultepec, a massive stone fortress on

top of a hill about a mile outside the city proper. Defending Mexico City

were from 18,000 to 20,000 troops, and the Mexicans were confident of victory,

since it was known that Scott had barely 8,000 men and was far from his base

of supply.

Scott

proposed an armistice to discuss peace terms. Santa Anna quickly agreed; but

after two weeks of fruitless negotiations it became apparent that the Mexicans

were using the armistice merely for a breathing spell. On 6 September Scott

broke off discussions and prepared to assault the capital. To do so, it was

necessary to take the citadel of Chapultepec, a massive stone fortress on

top of a hill about a mile outside the city proper. Defending Mexico City

were from 18,000 to 20,000 troops, and the Mexicans were confident of victory,

since it was known that Scott had barely 8,000 men and was far from his base

of supply.

Molino del Rey, 8 September 1847.

On 8 September 1847, the Americans launched an assault on Molino del Rey, the

most important outwork of Chapultepec. It was taken after a bloody fight, in

which the Mexicans suffered an estimated 2,000 casualties and lost 700 as prisoners,

while perhaps as many as 2,000 deserted. The small American force had sustained

comparatively serious losses "124 killed and 582 wounded" but they

doggedly continued their attack on Chapultepec, which finally fell on

13 September 1847. American losses were 138 killed and 673 wounded during

the siege of the fortress. Mexican losses in killed, wounded, and captured totaled

about 1,800. The fall of the citadel brought Mexican resistance practically

to an end. Authorities in Mexico City sent out a white flag on 14 September

1847. Santa Anna abdicated the Presidency, and the last remnant of his army,

about 1,500 volunteers, was completely defeated a few days later while attempting

to capture an American supply train.

On 2 February 1848, the Treaty of

Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed, ratified in the U.S. Senate on 10 March 1848,

by the Mexican Congress in May. The

treaty called for the annexation of the northern portions of Mexico to the

United States. On 1 August

1848 the last American soldier departed for home.

In

return, the U.S. agreed to pay $15 million to Mexico as compensation for the

seized territory. This "seized Mexican territory" is the most controversial

issue in the Southwest history. Almost never delineated is the actual territory

controlled and not just claimed by Mexico or previously by Spain.

The

bravery of the individual Mexican soldier goes a long way in explaining the

difficulty the U.S. had in conducting the war. Mexican military leadership

was often lacking, at least when compared to the American leadership. And

in many of the battles, the superior cannon of the U.S. artillery divisions

and the innovative tactics of their officers turned the tide against the Mexicans.

The war cost the United States over $100 million, and ended the lives of 13,780

U.S. military personnel. America had defeated its weaker and somewhat disorganized

southern neighbor, but not without paying a terrible price.

1. Despite

early popularity at home, the war was marked by the growth of a loud anti-war

movement that included such noted Americans as Ralph Waldo Emerson, former

president John Quincy Adams and Henry David Thoreau. The center of anti-war

sentiment gravitated around New England, and was directly connected to the

movement to abolish slavery. Texas became a slave state upon entry into the

Union.

2. While it is

widely perceived in Mexico that the San Patricios defected solely on the issue

of religion, this myth is examined in a later chapter of Robert Miller's book:

Shamrock and Sword, entitled "Why they Defected". The fact that

there was rampant anti-Catholic bigotry in the US at that time does not play

as great a role in the formation of the unit as is believed in Mexico. Miller

states that the religious bond was not a main reason why many defected. The

attractive offer of high pay in the Mexican Army and the promise of land grants

to defectors after the war outweighed the fraternal bond over religion, according

to Miller.

A main reason

for their hero status in Mexico is derived from their exemplary performance

in the battlefield. The San Patricios ultimately suffered severe casualties

at the famous battle at Churubusco, which is considered the Waterloo for the

Mexican Army in this war. Mexican President Antonio Lopez Santa Anna, who

also commanded the armed forces, stated afterwards that if he had commanded

a few hundred more men like the San Patricios, Mexico would have won that

ill-famed battle.

Each San Patricio

soldier who deserted from the US side was interned after the war in Mexico

and subsequently given an individual court-martial trial. Many of the Irish

were set free, but some paid the ultimate price. Roughly half of the San Patricio

defectors who were executed by the US for desertion were Irish. Those Irish

who were released by American authorities did not return to the US; some stayed

in Mexico while most returned to Ireland, including John Riley who, surprisingly,

was spared execution.

Furthermore,

Miller makes it clear that the Irish deserters of the Saint Patrick's Battalion

were in no way representative of the Irish-born soldiers who made up one-fourth

of all enlisted men in the US Army during the US-Mexican War. There were seventeen

totally Irish companies who saw action in this war; many were highly decorated

units such as the Emmet Guards from Albany, New York; the Jasper Greens of Savannah,

Georgia; the Mobile Volunteers of Alabama; the Pittsburgh Hibernian Greens.

In 1959, the Mexican government dedicated

a commemorative plaque to the San Patricios across from San Jacinto Plaza

in the Mexico City suburb of San Angel; it lists the names of all members

of the battalion who lost their lives fighting for Mexico, either in battle

or by execution. There are ceremonies there twice a year, on September 12,

this is the anniversary of the executions, and on Saint Patric's Day. A major

celebration was held there in 1983, when the Mexican government authorized

a special commemorative medallion honoring the San Patricios.

In 1959, the Mexican government dedicated

a commemorative plaque to the San Patricios across from San Jacinto Plaza

in the Mexico City suburb of San Angel; it lists the names of all members

of the battalion who lost their lives fighting for Mexico, either in battle

or by execution. There are ceremonies there twice a year, on September 12,

this is the anniversary of the executions, and on Saint Patric's Day. A major

celebration was held there in 1983, when the Mexican government authorized

a special commemorative medallion honoring the San Patricios.

The Infantry flag made by the nuns at San

Luis Potosi is described as "The banner is of green silk, and on one side

is a harp, surmounted by the Mexican coat of arns, with a scroll on which

is painted 'Lebertad por Republica Mexicana". Underneath the harp is the motto

"Erin Go Bragh'. (Ireland Forever) On the other side is a painting made to

represent St. Patrick, his left hand a key and in his right a crook or staff

resting upon a serpent.

This is the flag captured at Churubusco

by the 14th US Infantry and later apparently taken to West Point and placed

in the chapel. But, it did not survive because when President Truman returned

the captured Mexican War flags it was not returned. The chapel was replaced

sometime in the 1930's and by then the flag seems to have vanished.

3.

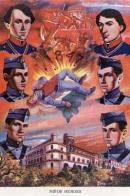

In Mexico, a special day is remembered to celebrate the bravery of the teenaged

military cadets at the military academy at Chapultepec Castle, which was attacked

by Scott's army on September 13, 1847. "Dia de Los Niños Heroes de Chapultepec"

(day of the boy heroes of Chapultepec), is commemorated every year on the

anniversary of the battle.

Seated

high on a hill, Chapultepec Castle had once been the resort of Aztec princes,

hence its fame as the Halls of Montezuma. Since 1833, it had served as Mexico's

military academy, and the cadets now fought side by side with seasoned soldiers

in heroic defense of their castle and country. Six of the youths died, one

clutching the Mexican flag to keep it from American hands. For their valor,

they have been honored in annual celebrations as Los Niños Héroes. Ordered to retreat by their Commandant,

these young cadets joined the fight- the boy heroes who are honored every

year are the four teenaged cadets (Francisco Marquez, the youngest, was thirteen

years old!) and their lieutenant squadron leader, Juan de la Barrera, (the

oldest, age 20), who lost their lives in that battle.

Seated

high on a hill, Chapultepec Castle had once been the resort of Aztec princes,

hence its fame as the Halls of Montezuma. Since 1833, it had served as Mexico's

military academy, and the cadets now fought side by side with seasoned soldiers

in heroic defense of their castle and country. Six of the youths died, one

clutching the Mexican flag to keep it from American hands. For their valor,

they have been honored in annual celebrations as Los Niños Héroes. Ordered to retreat by their Commandant,

these young cadets joined the fight- the boy heroes who are honored every

year are the four teenaged cadets (Francisco Marquez, the youngest, was thirteen

years old!) and their lieutenant squadron leader, Juan de la Barrera, (the

oldest, age 20), who lost their lives in that battle.

Notes and sources:

1.

Kohn, George C. Dictionary of Wars. New York: Facts On File

Publications. 1986.

2.

Eisenhower, John S.D. So Far From God: The U.S. War With Mexico 1846-1848.

New York: Anchor Books, Doubleday. 1989.

3.

Winders, Richard Bruce. Mr. Polk's Army. Texas A&M, 1997.

4.

Frazier, Donald S., ed. The U.S. and Mexico at War: Nineteenth Century

Expansionism and Conflict. Macmillan Library Reference, 1998.

5.

Lee, R. "The History Guy: The Mexican-American War"

6.

Miller, Robert R: Shamrock &

Sword