By Roy Cook

Indian summer, fall in San Diego County, is a beautiful time. As dusk lengthens the mountain shadows, the air becomes crisp. There is stillness in these valleys. At DQ campus Sycuan this stillness is filled with anticipation.

|

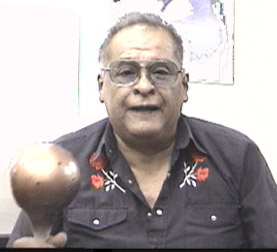

Jon Meza Cuero is a singer, native speaker, and culture bearer with lifetime of traditional experience in Southern California, Baja tribal communities. He is the traditional song teacher this fall 2001 semester. He sings Nyemie, wildcat, gato songs. His demeanor is respectful and gentle. Jon is not only a culture bearer but, most significantly, he is a window to a different frame of reference. Unique life circumstances have positioned him to be this portal. He has told us he was born in the Potrero area of South San Diego County. In addition to early traditional instruction in Tipai language he received special attention in wildcat songs. He has participated, with other respected members of the Kumeyaay community, in the regional favorite peon games for high stakes. |

|

| He is a popular and requested singer in many of the Northern Baja California tribal communities. His commitment to the survival and preservation of Tipai language and traditional song is well documented in the Native American community. Actually, Jon is accomplished in more than three dialects of Tipai and has a working knowledge of Pai Pai and Kiliwa. He is very encouraged by traditional avenues and proper protocol. |

In our first class, after introductions and coffee, Jon is listening and evaluating. Students sing from a tape by Leroy Elliot that was obtained through the previous class. We continue to sing a couple more songs.

We talk about what we have been doing this past summer, singing on our own, and what has brought us to this point together. Jon asks to use one of the extra gourds and off we go!

Much is the same, everything is different. Gourd position, movement of the gourd, structure of the song and frequency of the lifts. Even so, the strength of the song is such to overcome this unpredictability. These are great songs! We like what we hear. We try harder to 'catch' the tune. Many of the words are familiar. It is becoming fun. We beam with smiles all around as we work to be a part of the song. We feel we are living the Waimie experience. Jon is patient and assuring to us, now, 'his' students.

He offers us his best songs, unconditionally and encouraging in his comments. His attitude is open and relaxed toward technology. He simply states, "These are my songs and all who hear or have heard them know whose songs they are." This is a very generous and enlightened perspective of a confident teacher. Fifteen weeks of learning Tipai Nyemie Traditional songs have presented views and obligations that will long be a responsibility of these fortunate students at DQ-Sycuan.

This following brief description is part of an observation I was privileged to experience as a result of performing a small favor for our teacher Jon Meza Cuero. VHS tape private collection; "Kuri kuri scene; two youths singing-Jon in background-Young dancers in foreground. Song is Wildcat, clearly one of Jon's songs. This scene is the image of hope and the future assured. It speaks volumes to the continuity of the Native American culture. It is a vital and momentous statement in a metaphorical context. The setting and the size of the group are both poignant and compelling. This clip 'of the future' allows us to view the images of an earlier time in the context of today.

Additionally, these and other images speak volumes to the Native American Tribal Validity south of the imposed border regardless of geographical and political proximity of other influences (USA, Canada, and Mexico). With this reality, let us hope the unfounded maliciousness of prejudice and bias will no longer be supported by ignorance."

Review of Nyemie song class- Fall, 2001 By Roy Cook, student

Our teacher is adamant about establishing the historical character of the Wildcat songs. Jon has often said,

" I learned these songs from my Father when I was seven years of age. At that time my father was 85 years of age. He learned the songs from his father when his father was 85 years old. I am now seventy-five. How many years is that?" At first, I thought this was a rhetorical statement. Upon reflection I can recognize my error in perception. One of the constant qualities learned from participating in tribal song and association with tribal singers and lead singers in particular is a sense of singer/song territoriality. Many lead singers establish their 'credentials' to present their repertoire by acknowledging their debt to those who taught them the songs.

|

In this, Southern California region, there are respected elders who recall this style of singing and may have the ability to support the presentation, but will not attempt the task without a lead singer. (I must respect their choice to not be listed in public.) Jon Cuero, by circumstance and politics, is a participant observer of the dynamics at work defining traditional song style in the Kumeyaay, Ipai, Tipai and extended territory. As a teacher, Jon strongly emphasizes the need to learn the tune first. He has often said, "First the song, then the words, and then what the words mean." |

We feel there are literal meanings to the words and allegorical significance

that extend beyond the basic level. We can only hope to glimpse this world

of rich imagery and epic journey by cultural hero and trickster tales.

Humans can remember for long periods. They remember who they are and where

they come from. They remember critical events like great floods and star

bursts. They remember where they were created. If they move (or migrate)

to a very different ecosystem they remember the move and the painful process

of learning how to succeed in a new homeland.

For example, Keith Basso's recent book Wisdom Sites in Places (1996)

documents how some tribal people not only record stories, teachings, and

events by attaching them to a landscape feature, and even further by giving

that feature a meaningful name. He also documents how they order this

knowledge chronologically, to preserve the history of changes in their

interaction with the landscape, from the time they arrived to the time

they finally reached settled life (Keep in mind this movement is more

often levels of continuousness than physical movement}.

Oral history is much more than just words. Emory Sekaquaptewa (a Hopi

lawyer and tribal judge) says that for the Hopi, oral history is behavioral

performance tied to symbols, music, singing, and place; it is not about

telling campfire stories to children but about teaching them how to organize

their everyday life. History is encoded in ritual. Brasso's Wisdom

Sites in Places indicates that performance and landscape often are

closely connected. Therefore, if a people remain in their creation lands

they will continue to detail events and orally weave a tightly woven basket

holding those song and stories that remember who they are, where they

came from, and what has happened to them. If they move, they remember

where they were and how they came to be where they are now. However, the

songs are much more elegant than I will ever hope to be.

SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA GOURD RATTLE CONSTRUCTION Click

for Review